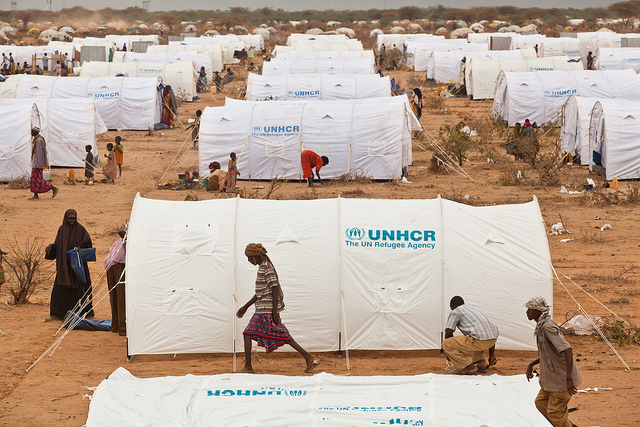

As the international community prepares to address the ongoing needs of the global refugee crisis at the World Humanitarian Summit later this month, it got a nasty surprise last week when Kenya announced it would be closing the Dadaab refugee camp in central Kenya.

Read MoreWritings

The ICC's Rough December

It has been a rough month for the International Criminal Court. A week after deciding to withdraw the charges in the high profile case of Uhuru Kenyatta, the ICC’s Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda appeared before the UN Security Council to inform them that the court will be suspending investigations into atrocities committed in Darfur due to a lack of cooperation by the Sudanese government, ICC member states and the UN.

Read MoreHow Witness Tampering Fatally Undermined ICC Prosecution of Kenya’s President

Yesterday ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda took the extraordinary measure of filing an application to indefinitely adjourn the trial of Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta in order to seek additional evidence to sustain the prosecution. At the core of the request is the ongoing issue of witness tampering that has haunted the ICC in Kenya for years.

Read MoreThe Battle Over the Future of the ICC Continues in The Hague

The annual Assembly of State Parties of the ICC (ASP) kicked off yesterday to discuss the management of the court and possible changes to the Rome Statute. While several issues are on this year’s agenda, including victim compensation and progress on ratifying amendments to define the crime of aggression, chief among the concerns of the state parties are the issues surrounding the current cases with Kenya and in particular the prosecution of President Uhuru Kenyatta and Vice President William Ruto.

Read MoreKenya Votes While Calm Reigns

In the spring of 2008, I met with a group of Kenyan human rights activists to discuss what they saw as the most pressing issues in East Africa. At one point, the conversation turned to the post-election violence their country witnessed just a few months before. “I know,” one of them said, shaking her head. “It’s really bad. It hasn’t been this bad since the last time it happened.”

Indeed.

It is often said that the 2007-2008 post-election violence took many people by surprise but if that’s true, they weren’t paying attention. In the background of this week’s presidential election is not just the 2007-2008 post-election violence but the fact that every presidential election since 1992 – the first multiparty elections the country held – involved political violence. Thus while some in Kenya may mock the concerns international media published leading up to the election, the concerns are not without basis. What Kenya is facing is not just the overcoming of embedded political corruption, but the need to change a political and social culture that places ethnic identity at the forefront of national politics.

And so far, Kenya is succeeding. While the March 4 election was not without incident, the violence witnessed on election day was limited to separatists who rejected the entire notion of the election rather than divisions between different ethnic groups and political camps as previously seen. Things may change – at the time of this writing, only about half of the votes are counted and the results are far from definitive, especially given the problematic issue of spoiled ballots – but it appears that Kenya has managed to break from its past. Here is a small look at what happened from 2007 to today.

International Pressure

There are numerous ways the international community engaged Kenya over this issue in the last four years but the most obvious involvement comes from the ICC. Unlike previous elections, the 2007-2008 violence led to a power-sharing agreement brokered by Kofi Annan that notably allowed for a referral of the issue to the ICC if the Kenyan parliament failed to establish a national tribunal to handle post-election violence cases by a set deadline. Despite concerted efforts to establish such a tribunal, in the end parliament voted against the tribunal leading to a referral, investigation and four confirmed ICC indictments against Kenyan political figures for the violence.

The issue of the ICC and Kenya is an interesting one given the nature of the referral and the fact that two of the accused, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto, represent the presidential ticket for the National Alliance party. But despite complaints by those accused, opinion polls show that Kenyans are generally favorable towards the ICC as they don’t fully trust their own government to pursue justice.

Currently, Kenyatta and Ruto are leading in the polls. If Kenyatta does win the presidency, there will clearly be some awkward days ahead as he becomes the second sitting head of state behind Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir with an active ICC indictment. But for now the ICC indictments have ensured that the post-election violence issue stayed at the relative forefront of international affairs rather than buried in favor of more immediate concerns like Kenya’s cooperation in fighting Islamist militants in Somalia. That focus means that international pressure for reforms has not lessened even with the passage of time and placed greater urgency on both the government and the people to find proper solutions to avoid a repeat of 2007.

Government support of reforms

Real change requires commitment from within. As noted above, there have been fits and starts in the reform agenda but overall the government and all the related parties supported reforms as part of theKenya National Dialogue and Reconciliation process established in 2008. Parliament passed several legislative pieces as part of this framework including the creation of a National Cohesion and Integration Commission, a review of the 1969 constitution and a successful referendum on a new constitution in 2010 that established an independent electoral commission. Public statement against violent episodes in the Tana Valley and potential hate speech helped dissuade tensions in the buildup to the elections while forging a new political outlook. Although numerous reforms are still needed on issues such as police accountability, land reform and poverty reduction, the progress Kenya has made in just four years is encouraging.

“People Power”

Yet the biggest reason why violence did not reoccurred is because of ordinary Kenyans. From theatre groups to youth outreach programs, Kenyans embraced opportunities to advance dialogue and encourage peaceful elections. Ushahidi, the crisis mapping platform created in the wake of the 2007 post-election violence is now an internationally known non-profit with extensive experience in crisis mapping; to prepare for elections this year they launched Umati to track potentially dangerous hate speech in the lead up to the polls and Uchaguzi to track potential violence and corruption through citizen reports. The combination of grassroots organizing with local technology made it harder for violence and corruption to go unnoticed. It also gave ordinary people a direct role in preventing future violence and the ability to shape the final outcome.

These are just some examples of the local initiatives spearheaded by Kenyans to encourage democratic progress. However what they highlight is that while media reports going into the elections carried the narrative of possible catastrophe, they also carried the narrative of a people determined to learn from the past and avoid the same mistakes again. At this point, it looks like the will and efforts of the people won.

What can we learn and where do we go from here?

First, the success of this election belongs to Kenyans. In the last four years, the government, local and international NGOs as well as ordinary individuals have worked to acknowledge the pain of the past while also giving citizens an understanding of their role in changing the outcome. From the grassroots to the upper workings of government agencies, Kenyans worked hard at building connection, understanding and transparency to avoid the mistakes of previous elections. There are still areas where improvements can be made, but the last four years marks a huge step in the right direction.

Second, process matters. The passage of a new constitution with stronger election requirements and the creation of an independent election commission immensely helped transparency. Numerous Kenyan media websites are carrying running tallies of the votes based on information released by the electoral commission, informing people in realtime of the vote count. Doing so aids in transparency and gives people more confidence in the result. This is a dramatic difference from previous election processes in Kenya which lacked transparency and election processes in some other African countries also facing elections this year like Zimbabwe. So far, Kenyans online have expressed far more optimism and confidence in their election than anyone I’ve heard from Zimbabwe. There are many reasons for this but a big one is that process does in fact matter.

Third, it must be remembered that the election itself is just one step in an ongoing democratic process for better governance and accountability. The election has not been without difficulties, including hundreds of thousands of spoiled ballots that are not counted towards any candidate. This presents the first wrinkle in an otherwise positive election and could cost Kenyatta an outright victory by forcing a run-off. Further investigations need to be done to understand why there are such a large number of spoiled ballots in order to avoid it in the future. Whether they are the result of corruption or innocent mistakes by voters and officials, the result means that hundreds of thousands of Kenyans are being disenfranchised. That does not bode well for Kenya or its democratic credentials.

There are also signs that Kenyans are still voting largely along ethnic and regional lines. This is somewhat to be expected; people typically vote for who they feel will best represent them and someone from the same region or tribe will often feel more representative. But this voting pattern makes for big winners and big losers among the population, one major factor leading to previous election violence. This election’s trend of building cross-tribal political coalitions helped Kenyatta and Ruto but also holds the potential for a “tyranny of the majority” mindset by the subsequent government where losing tribes are further marginalized by the government. If that indeed comes to pass, it will undermine the general credibility of democracy in Kenya. Thus the election is just step one; engaging the population across ethnic and regional lines is still necessary both in the actual government and hopefully to be better addressed in future elections.

In the meantime, the international community needs to provide its support to the outcome and ongoing election process. This is especially important if this week’s election results in a run-off. As Kenyans prove their detractors wrong, the very least the international community can do is support those efforts and give credit where it is rightfully due.

Originally published by Foreign Policy Association

Balancing Justice & Politics in Kenya

In an ideal world, the search for justice would always trump the pragmatic workings of politics. However rarely do we live in that world. Instead amnesties are granted in the hopes of a peaceful regime change, dictators are allowed to flee their counties for the permanent and well financed exile while their victims remain to put back together what oppressive policies and violence broke. If enough time passes, as Haiti is now discovering with Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, those who grossly abused their power can often act like nothing happen. Of course justice is pursued by some countries determined to make sure that past wrongs are answered to, but success in those endeavors typically requires strong support from allied countries or organizations like the UN. Even then, messy politics makes for messy justice; accusations of bias in prosecution and worries about the cost of proceedings given the typically small groups of suspects tried are common, as are serious questions about the value of such proceedings for both victims and the political process. This, and not the ideal version we dream about, is the world we live in.

Recognition of these realities is one of the reasons why the International Criminal Court (ICC) took so long to come into being and is also a constant issue facing the court. In this battle between justice and politics, the biggest debate to date confronting the court is that of Kenya where it is believed high ranking politicians were involved in promoting the post-election violence that gripped the country in early 2008. The possibility of an ICC investigation was part of the agreement reached between President Mwai Kibaki and opposition leader (now Prime Minister) Raila Odinga, but was also contingent on the inability of the Kenyan parliament to pass legislation creating a domestic tribunal to try those responsible for the violence. After parliament failed to pass such legislation, the ICC opened an investigation and yesterday the decision on which of the “Ocampo Six” – the six people deemed most responsible for the violence – would be tried officially came down.

This is where the politics gets messy. Not only was the post-election violence largely divided on ethnic terms which ended in a fragile peace, but the members of the Ocampo Six were and remain prominent political figures. For example, Uhuru Kenyatta is the current Deputy Prime Minister, Kenya’s wealthiest citizen and the son of the country’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. On the other side is William Ruto, the former Minster for Higher Education and a prominent opposition politician. Both Kenyatta and Ruto enjoy significant support with their rural constituents and both have stated they would be running in the presidential elections later this year. Politically, these two are positioned on opposite sides of the conflict but may be facing the same fate. Unfortunately, they also have the ability to take down all of Kenya with them. Again, this is the world we live in.

So what is more important, justice or politics? By ruling that four of the six charged would stand trial, including Kenyatta and Ruto, the ICC stuck to their mandate and chose justice. Ahead of the announcement there was strong support for the court among Kenyans but also increasing fears that violence could once again break out. So far, that has not happened. But with politicians gearing up for their presidential campaigns and two of the major candidates now getting ready to stand trial for crimes against humanity, yesterday’s decision is only the start of this debate, not the end.

Originally published on Foreign Policy Blogs

Inked after voting, South Africa, 2009 by Darryn van der Walt

The electoral disorder of 2010

Among other things, 2010 marked a number of national elections gone wrong. From Guinea to Haiti,Rwanda to the Philippines, Madagascar, Burundi and Belarus to name just a few, elections that were fair, free, non-violent and undisputed have been difficult to find this past year. Even elections in the US and UK took on more vitriol than is common, illustrating that bad politics really does exist everywhere.

These events raise several questions regarding the democratic order: what is the responsibility of the international community in guaranteeing that the will of a people be honored? Is democracy truly a universal political system? Does the sovereignty of states preclude international involvement in domestic elections? These questions have always existed but the nature of more recent election violence is also raising the question of how should such things be dealt with.

Such questions are again at the forefront of the international news cycle as Cote d’Ivoire appears to be slowly sliding back to civil war following a presidential election last month that both incumbant President Laurent Gbagbo and opposition leader Alassane Ouattara claim to have won. Ouattara is widely accepted as the rightful winner outside of the country – including by the United Nations,ECOWAS, the African Union, and even the Central Bank of West African States. Indeed, each passing day of this crisis appears to bring more allies to the side of Ouattara and more impassioned calls for Gbagbo to step down. Yet Gbagbo continues to control the domestic media and enough military forces to cause serious problems, a fact proven by stories of torture and enforced disappearances, the re-emergence of death squads on the streets of Abidjan, and a rising death toll that currently stands at 173.

Coincidentally the electoral crisis in Cote d’Ivoire comes as the International Criminal Court earlier this month released the names of six suspects under investigation for the post-election violence that occurred in Kenya two years ago. The usefulness of the ICC waging into election disputes and the violence that follows has yet to be fully proven; some analysts hail it as a step forward in breaking the cycle of impunity that plagues many “democracies” and demonstrates the full power of the court while others worry that the case could have a destabilizing effect on the country which is progressing, albeit slowly, towards a more inclusive political system. Back in November when elections in Guinea were heading south, a letter from the ICC to the government noting that it was paying close attention to developments in the country may have helped bring about a resolution in that case. The end result there was the swearing in of Guinea’s first democratically elected president in over 50 years. However the reaction of the Kenyan parliament to the actual indictments, which have been a long time coming: anoverwhelming vote for the government to leave the ICC.

There are many reasons as to why it is unlikely that Kenya will actually leave the ICC. But as the situation in Cote d’Ivoire continues to deteriorate and the international community prepares for another contentious referendum in Southern Sudan next month, the issue of what power the international community has in ensuring just elections whose results are honored remains unclear.

What is clear to those following events in Abidjan and Nairobi is that these crises do matter, not just for the future of the countries at hand but also as a test for African leaders to uphold the basic promises of democracy and rule of law. The election in Cote d’Ivoire comes at the end of a peace process designed to heal ethnic and geographical wounds spurred on by previous governments and colonial policies. If allowed to fall apart, West Africa may see the type of genocidal violence normally reserved for their central African neighbors. In a region that admittedly still has a long way to go, the progress West Africa has made in the last ten years in moving away from conflict could be derailed by one man not conceding defeat and urging his followers to do the same. Likewise, failure to address the fundamental issues behind the election violence in Kenya will only serve to encourage the same behavior, a cycle that threatens the regional stability and human rights movement of East Africa. Both examples demonstrate the need for a strategy to encourage the peaceful handover of power when the ruling party loses, a phenomena not completely unknown in these parts but far too uncommon.

Thus, 2010 marked a year when the will of the people often took a beating for the sake of those in power and the rest of the world was left wondering what to do about it. Those questions still remain, but some of them may be answered as the situation in Cote d’Ivoire continues to unfold. However, to be fair while there was no dearth of elections gone wrong in 2010, the year also had its bright spots. As mentioned above, Guinea salvaged its national election to open up what many hope will be a more democratic chapter in that country’s history. And though largely a sham, elections in Burma, the first in 20 years, did see the release of pro-democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest while the election of the first right wing government in Chile since Pinochet demonstrates how far they have come since those dark days. For the international community, these examples are worth remembering as we enter 2011 and get ready for potentially volatile elections in Sudan, Niger, and Zimbabwe as it illustrates the existence of light even in the seemingly darkest of tunnels.

Originally published on Foreign Policy Blogs