As no Year in Review would be incomplete without a list, here are some of my top picks for 2011:

Most Unexpected event

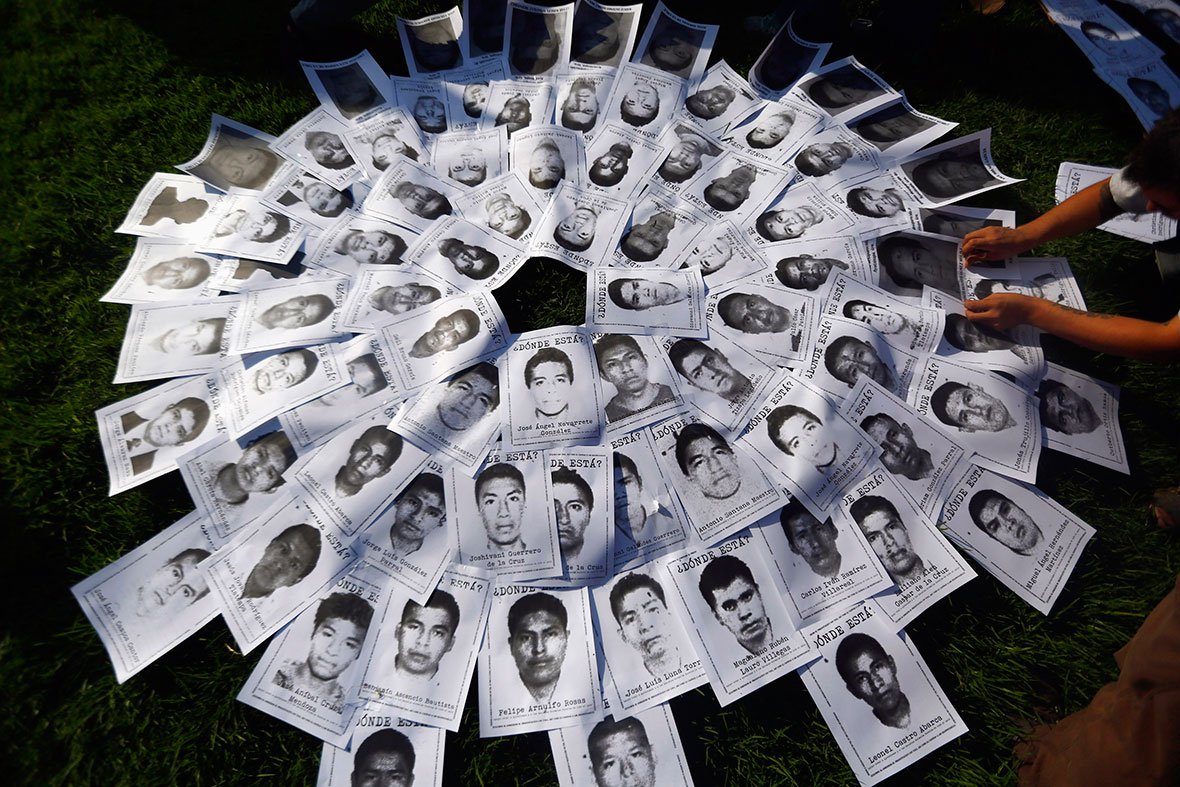

As I noted at the start, this year has been an incredibly active one for protests, the type of year that probably hasn’t been seen since 1968. Even still, 2011 has been more remarkable in many ways because of the diverse locations where these movements have sprung up and in how they built upon each other throughout the year, aided by relationships forged through social media and increased global communications. While analysts may have suggested that major uprisings or protests were due in some of these countries for a while, I doubt that any of them would have – or even could have – predicted the way these protests merged and multiplied, both online and in the streets. There is no single name for this trend or phenomenon, but that is my choice for most unexpected event of the year.

Most important person or group

Closely related to my choice for most unexpected event, my pick for the most important person or group is actually a generation. Whatever you choose to call them – Generation Y, Millennials, Generation Next, or some other iteration – their presence has been undeniable in shaping major events of the past year. In 1966, Robert F. Kennedy gave a speech at University Cape Town where he memorably stated, “Few will have the greatness to bend history, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events. And in the total of all those acts will be written the history of a generation.” After years of being mostly defined by their consumer habits and entertainment choices, this past year saw this generation find its voice against injustice, as well as the courage to work towards a different world.

Book of the year

My choice for book of the year highlights the aborted Persian Spring rather than this year’s Arab Spring. “Then They Came For Me” by Maziar Bahari tells of his months in Iran’s infamous Evin Prison for his journalistic coverage of the 2009 Iranian Election Protests. While his period in prison was Kafkaesque at times, the story also highlights the humanity of the protestors and ordinary Iranians in their search for dignity in a country that they love.

What to look for in 2012…

While 2011 was a major game-changer in some ways, on the other hand I find that my outlook for 2012 is not much different from what I predicted last year. I’m comfortable with that since much of what I predicted for 2010 came true this past year (and being only a year off is fine with me).

Digital rights and what freedom of expression means in the 21st century will continue to be a major human rights issue, especially after the EU quietly passed the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Act earlier this month and the possibility that the US House of Representatives will pass the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) in the new year.

Likewise protests are also likely to continue in 2012. The four countries that managed to overthrow their dictators this year – Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen – still face significant battles in stabilizing their governments and bringing about a full democratic transition. Protests and subsequent crackdowns by the government continue in both Bahrain and Syria, with no end in sight for either. The only country in North Africa to largely escape the protests that swept the region is Algeria, but already some are predicting that may change soon. Similarly, the Occupy movement is determined to not fade away in the new year as they come up with new methods of protest even as many of their camps are disbanded. As this past year demonstrated, protests movements in one corner of the globe can bring about new movements elsewhere, so what is in store for 2012 remains a mystery to even the most astute analysts.

Corporate involvement and influence in politics is also likely to be an ongoing issue. This is the central focus of the Occupy movement, but there have been other indications that more people are focusing on corporate accountability as well. In particular, the increasing evidence of Western technology firms selling surveillance equipment to repressive regimes have raised new questions about what responsibility for-profit organization have in the consequences of their products. Elsewhere, there is growing attention on the long term impact that increased involvement of Chinese firms in Africa may have for both political and economic democracy in the region and the growth of human rights. No matter where you look, corporations are facing more scrutiny which in unlikely to go away anytime soon.

In the end, what I am left with in the final hours of 2011 is how much more optimistic I am about this coming year than I was last year. So much has happened in the past 12 months that it can boggle the mind. But while some events were heartbreaking, most of the past year has been uplifting and at times, even inspiring. If 2011 was the year when “human rights went viral” then it is now on us to make 2012 the year when the world finally consolidated those rights and made them count.

Originally published on Foreign Policy Blogs