As the international community prepares to address the ongoing needs of the global refugee crisis at the World Humanitarian Summit later this month, it got a nasty surprise last week when Kenya announced it would be closing the Dadaab refugee camp in central Kenya, widely considered to be the largest refugee camp in the world with over 350,000 people calling it home. It is easy to be critical of the Kenyan government for making this decision, but it is just the latest sign that the current approach to refugees is unsustainable and the international community as a whole needs to rethink the way we approach refugees.

Although the Middle East and Europe have garnered most of the recent attention on refugees, the region hosting the most refugees is actually Africa. Recent conflicts in northern Nigeria, South Sudan, Burundi and the Central African Republic have added to these numbers, but protracted situations in Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda have also contributed large numbers to the estimated 3.6 million refugees on the continent.

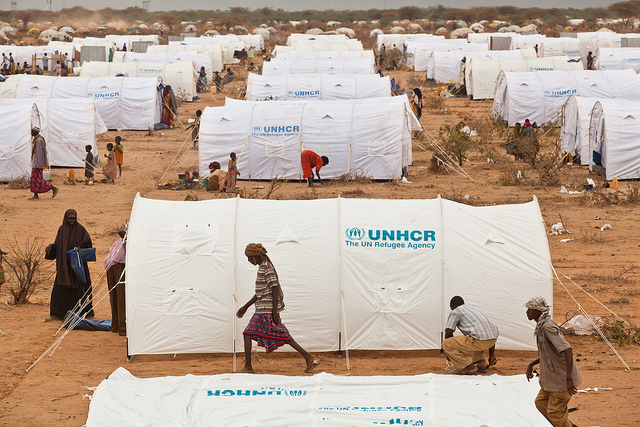

Kenya hosts over 600,000 refugees, many of them in the longstanding Dadaab and Kakuma refugee camps that have hosted mostly Somali and South Sudanese refugee for decades. Although the camp at Dadaab started as a temporary transit station to process Somalis fleeing drought and that country’s civil war in 1992, it soon grew into a sprawling network of camps, hosting nearly 500,000 people at its peak in 2011. The size of Dadaab means it is one of the largest cities in Kenya, if it were in fact a city. Despite substantial aid given to Kenya to help host the camp, it still constitutes a major social, political and economic cost for the government.

This is not the first time Kenya has threatened to shut down Dadaab. For some time, Kenya has questioned whether the cost of hosting these refugees was worth it. Recent attacks by the Somali militant group Al Shabaab at theWestgate Mall in Nairobi in 2013 and Garissa University in 2015 increased anti-Somali sentiments, and by extension Dadaab, throughout Kenya. Even though no real evidence has emerged linking Dadaab to any of the recent attacks, the camp and its inhabitant became an easy political target for the Kenyan government who was looking to deflect attention from it’s the actions of its own security forces in the aftermath of Westgate and Garissa.

But the lack of evidence linking Dadaab to recent attacks does not mean the camp does not pose a possible security problem. The longstanding nature of Dadaab and the ongoing troubles in Somalia means that there is an entire generation who has only known the camp since birth, and knows little of the world outside its perimeter. They are not truly citizens of any country and many have no home to go back to. With few opportunities and even fewer prospects at a life outside the camp – which itself exists in a kind of existential void – life in Dadaab is the type that breeds poverty, resentment and possibly extremism; in other words, while the camp has not threatened the security of Kenya yet, the conditions there might make that a case of when, and not if, such camps become a launching pad for violence and extremist groups.

Part of the blame for this falls on Kenya, which has done very little to try and integrate Somali refugees into Kenyan society even once it became clear that they were here to stay. But the lack of attention and desire by the wider international community to come up with a real solution to long-term refugee situations is also to blame.

While industrialized countries often foot the bill for camps through direct aid and UN appeals, it is developing countries who actually host almost 90 per cent of the refugees in the world. Although refugee camps are considered to be temporary, it is far more common for refugees to languish for decades in the makeshift tents. Unable to return to their home countries out of fear for their personal safety but not able to move forward in life with regular educational or employment opportunities, refugee camps essentially put a person’s life on permanent hold, often for years. Known as “warehousing”, it has been a problem for long before the current crisis in Syria. The situation takes a serious emotional toll on refugees, but also makes it that much harder for them to integrate into host societies or reintegrate back into their home countries once a conflict has ended.

This is why more and more people are calling on the humanitarian sector to rethink refugee camps and the way long term refugees are treated. Perhaps more than any other location, Dadaab represents the costs of warehousing but also the challenges of going forward. Closing the camp without adequate alternatives in place will likely only make things worse and could create an even bigger security problem for the region. More importantly, it will place hundreds of thousands of people entitled to the world’s protection at risk as part of a political power play that the people at Dadaab have no role in.

This last point is why soon after the Kenyan government announced the planned closure, the condemnations started to come in. Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Refugees International and countless other NGOs issued statements warning of the risks of kicking out more than half a million refugees and sending them back to the war zones that they came from. But the announcement and reaction comes at a time when Western governments are actively shirking their responsibilities when it comes to refugees.

Recent court decisions in Australia to maintain offshore detention for asylum seekers and the controversial EU-Turkey deal to return refugees to Turkey support warehousing, albeit it in other countries. In such a climate, criticizing Kenya for ending decades of support to Dadaab is likely to fall on deaf ears because the hypocrisy surrounding the treatment of refugees in the midst of the current global crisis.

This hypocrisy is unsustainable, as is the current model for dealing with refugee flows. While Dadaab may be the model example of why things need to change, it is not the only camp where these issues persist. Given the events of the last few years, Kenya’s announcement last week is disappointing, but not surprising.

What is more concerning is that nearly 50 years after the Refugee Convention went global, Kenya may just be the first of many governments who decide enough is enough, and opt to ignore the world’s most vulnerable people.

Originally appeared at UN Dispatch